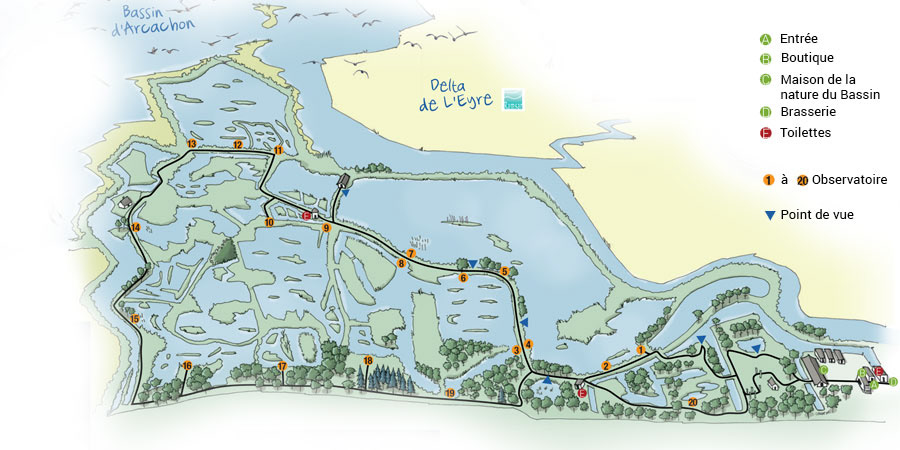

The first reserve we visited, the Teich Reserve ("Réserve du Teich" in french) is located on the south shore of the Bay of Arcachon, around forty kilometers south-west of Bordeaux. Created in 1972, it is organized a bit like the Marquenterre reserve in the Baie de Somme, with a 6 km trail winding through woods and waterways, and some twenty observation points offering close-up views of the resident birds.

I was dazzled by the richness of the fauna, starting of course with the number and variety of bird species observable along the reserve's paths.

For several years, I had wanted to observe and photograph Green-winged teals (Anas Crecca) and Northern shovelers (Spatula clypeata) up close. My previous attempts had been unsuccessful, and I'd only been able to observe from a distance the colorful wingbeats of fledging shovelers, and the “swarms” of tiny teal, whose abrupt flight direction changes make them look like waders. For some reason, the birds at Le Teich were less shy; not that they could be approached like mallards at a pond, but I was able to photograph some of the shovelers less than twenty meters away, while only poorly hidden by a few etic reeds.

Shovelers and Green-winged teal are the most common anatidae on the site. The number of resident ducks is indicated on a board at the entrance to the reserve; I don't remember the figures very well, but it seems to me that at the time of our visit the estimated number of shovelers and teal was close to a thousand for each of the two species, a significant figure when you consider that the total number of shoveler ducks in France is around thirty thousand.

Unlike mallards, which love the small ponds, inlets and canals linking the reserve's various ponds, Northern shovelers are confined to the largest expanses of water, which offer them better protection from potential predators. They mix happily with green-winged teal, splashing about in the floating grasses that are their main winter food. Groups often number several dozen individuals, with the two species coexisting peacefully apart from occasional neighborly conflicts, which invariably end with the tiny teal's retreat.

It's a pleasure to watch these ducks flying in clouds over the reserve's lakes. The male shovelers are particularly splendid, their wings sporting a bright blue patch on the front, while the back is pure green. I still remember, in the summer of 2021, my first sightings of colossal flights of hundreds of Northern shovelers over lakes south of Berlin, where I lived at the time. At the time, I was unaware of the existence of eclipse plumage in ducks, and couldn't identify this bird with such colorful wings, but the rest of its plumage reminded me nothing of the photos of shovelers with their “normally” green necks...

In addition to these two species, I also had the opportunity to observe Northern pintails (Anas acuta) for the first time in my life This is a magnificent duck whose male proudly sports a long, tapering tail and a brown mask contrasting with a brilliant white breast. At the time of my visit, the reserve was home to a few dozen individuals, usually in pairs and not in groups like the teals. Pintails are wary, but the presence of observatories significantly reduces the viewing distance. Like the shoveler, the pintail is a species that only winters in France. In spring, it migrates to Northern Europe, where it breeds. Wintering populations in France are limited, with between ten and twenty thousand individuals spending the winter here. Given that the coastline of mainland France is 5,500 kilometers long, spotting one is not that easy.

Another first for me _ Black-tailed godwits (Limosa Limosa). Magnificent waders, among the largest in their family, they are represented by three subspecies in Europe. The subspecies L. l. limosa, which winters in Africa, nests exceptionally in France, with barely a hundred breeding pairs recorded, mainly in the Vendée region. Its cousin L. l. islandica, which, as its name suggests, nests in Iceland, winters in France in much larger numbers (around 30,000 individuals), particularly in their stronghold in the Baie de l'Aiguillon. This is the subspecies we observed in the Réserve du Teich.

Like many other shorebirds, the Black-tailed Godwit has been suffering from the ever-increasing impact of human activity on its habitat. For example, breeding numbers in the Netherlands, which accounts for almost half of all European breeding birds, have fallen by 75% over the last 30 years. A similar trend can be observed in other countries such as Germany.

A fact that astounded me (though perhaps not so exceptional among birds?) is that, despite their thousands of kilometers of migration, the majority of these godwits come to breed within five kilometers of their birthplace. A fact documented in fish such as salmon and eels, this innate ability to find one's way back to one's birthplace never ceases to fascinate me. One day, we'll probably find a scientific explanation for what we've come to call “instinct” ... until then, let's contemplate and marvel at these mysteries that we might still believe to be supernatural.

A fact that astounded me (though perhaps not so exceptional among birds?) is that, despite their thousands of kilometers of migration, the majority of these godwits come to breed within five kilometers of their birthplace. A fact documented in fish such as salmon and eels, this innate ability to find one's way back to one's birthplace never ceases to fascinate me. One day, we'll probably find a scientific explanation for what we've come to call “instinct” ... until then, let's contemplate and marvel at these mysteries that we might still believe to be supernatural.

I could not make nice shots of godwits. Relatively shy, they were reluctant to get close to the hides.